The Vibes are Off in Outback Steakhouse

Identity and nation-making in American's favorite Australia-themed eatery

After seven years on the drug, I’ve been weaning myself off of Lexapro with the lofty goal of (re)discovering who I am, and so it is difficult to say whether my first dining experience at the Outback Steakhouse at the Capitol City Mall is rooted in something as impalpable, albeit ineluctable, as shifting chemical balances or many somethings that, while equally nebulous, are grounded somewhere in the world outside of myself.

My wife is notorious, at least to me, for experiencing strong rushes of desire which, at the moment of their articulation, seem to have sprung from nothing and nowhere. These desires are typically organized around particular foods which, more often than not, share no place in our regular diet, but rather stem from specific, long-ago experiences that have survived in such a period of extended dormancy that, when they do come back to life, they do so with the kind of force and extravagance that make me feel as if I am witnessing some variety of phenomena which I cannot understand, but only marvel at. Sometimes it’s gravy that she wants. Other times it’s pumpkin ravioli. The desires are always specific and, usually, ephemeral. However, recently, we were lying on the sectional in our living room when she turned to me and, as if possessed by the craving itself, said she wanted to go to Outback Steakhouse to eat a Blooming Onion, a salad with ranch, and a steak with a baked potato. I had never been to an Outback, and she hadn’t eaten at one in over 15 years. Sometimes, to do a thing in life, the reasoning itself needs to be unassailable, with every angle and potentiality having been so thoroughly considered that the act of finally making a decision feels like a relief from the relentless calculus that underlies so much of the process of discerning how we should spend the meager currency of our time. This was not one of those times. On a Saturday afternoon in late October, fueled by the kind of ironic appetite which always belies a certain earnest yearning, we got into the car and drove an hour south to the nearest location.

The interior of the Capital City Mall Outback Steakhouse outside of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is largely indiscernible from other locations across the world. There are large, dark wooden booths and an island bar, walls adorned with Australian memorabilia and tables set with oversized silverware. For restaurant chains, homogeneity and predictability are features, not bugs. Customers should be able to have the same experience whether stepping into an Outback in Frisco, Texas, or São Paulo, Brazil. However, this kind of “McDonaldization,” a term coined by sociologist George Ritzer to describe the role of the fast food restaurant in structuring and mediating social life and individual identity, also produces the uncanny feeling that you are eating in a place not entirely of this realm, a simulacrum of a simulacrum of an idea built atop a feeling.

While it might seem obvious that a restaurant named Outback Steakhouse is in some way meant to connote Australian culture or cuisine, the connection hadn’t truly dawned on me until my wife and I were seated in one of the booths picking away at our Blooming Onion. On the wall opposite from us, there was a metal cutout in the shape of the country, though the interior was smooth and featureless, and it was in that nondescript expanse of the interior where the proverbial Outback lay. I asked my wife if she thought that people came to eat here so they could experience Australia. No, she said. No more than a person goes to Texas Roadhouse to experience Texas.

I agreed with her, though implicit in this simple truth is the underlying assumption that there is any one, real, and authentic way of experiencing a place. I’m from Texas, and there is a Texas Roadhouse not five minutes from our house in Central Pennsylvania, and never does driving past it remind me of home in any meaningful sense, and I’ve never felt compelled to go inside.

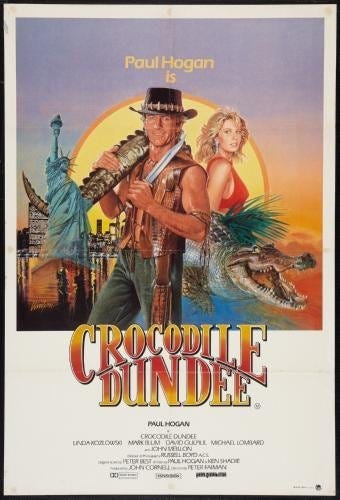

The first Outback Steakhouse opened in Tampa, Florida, in 1988, the same year of the Australian bicentenary, which marked 200 years since the arrival of the first British convict ships in Sydney, and the premiere of Crocodile Dundee II. These events, while temporally distant, marked two different stages in the process of the creation of Australia as an “imagined community.” As Benedict Anderson explained in his book Imagined Communities, a nation is an imagined community “because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.” Communities are not differentiated by variations of falsity or authenticity “but by the style in which they are imagined.”

In searching for a national identity, Australia was especially influenced by Russell Ward’s construction of “The Australian Legend,” which imagined typical Australians as rugged, masculine frontiersmen of the bush, a colloquial term derived from early 19th century British settlements in their description of the wild hinterlands. The release of Crocodile Dundee in 1986, a wildly successful box office hit starring Paul Hogan as an eccentric bushman living in Australia’s Northern Territory, was a further iteration and perpetuation of Ward’s “Australian Legend,” which traced the seeds of Australian nationalism back to the settling of its frontier by Europeans.

The handful of Americans that founded Outback Steakhouse, none of whom had ever been to Australia, viewed their personal unfamiliarity with the nation not as a hindrance, but as a boon. Chris Sullivan, one of the three founders, said, “Americans were fascinated with their notions of ‘the land Down Under.’ We were concerned that too much authenticity might cause a disconnect between these perceptions and the real thing.” More than anything, Outback Steakhouse was never meant to embody the “real” Australia. Rather, it is a decidedly American restaurant which utilizes perceptions of Australian society, popularized through Ward’s Australian Legend, to appeal to decidedly American audiences. The same can likely be said of Lone Star Steakhouse & Saloon, which first appeared in North Carolina in 1989 before later expanding to Australia in 1993, the same year that Texas Roadhouse opened its first location in Clarksville, Indiana. If there is a link between these chains, it is in their appeal to a pleasant and inoffensive mythos of the Wild West which, at its most potent, manifests as a vibe you get upon sitting down at a booth and opening the menu.

My wife ordered exactly what she’d planned to order: an iceberg lettuce salad topped with ranch, a six-ounce sirloin steak, and a baked potato. As she ate, she marveled at the fact that the meal tasted exactly as she had remembered it tasting 15 years before. I opted for the Toowoomba Salmon, a dish named after a small city near Australia’s Sunshine Coast, which came topped with shrimp and garnished with sides of rice and steamed, plain vegetables.

The more I ate, the more inexplicably sad I felt. In the booth behind us, an older woman remarked that both her salad and her alfredo were too spicy. The man with her told the manager his steak was also too well done, and the manager offered him the kind of assurance that was neither a commitment to correcting the issue or an official acknowledgement that there even was an issue to begin with. When I finished eating, I felt the kind of full that made me uncomfortable, and the remaining half of our Blooming Onion suddenly appeared to me as an alien thing.

The strangest aspect of weaning off of Lexapro has been the overwhelming feeling that something is wrong, accompanied by the immense uncertainty about whether that wrongness is a product of my own internal composition or such an external environment as the Capital City Mall Outback Steakhouse late on a Saturday afternoon when the space is only half-full with early bird diners and families who have spent the afternoon shopping. After we paid our bill and stepped outside, I had the distinct feeling that I had forgotten where I was both in space and time. This could be a positive feeling for some, the comfort that comes with knowing you can enter a particular establishment, no matter where or when you are in life, and suddenly find yourself in a space that is familiar.

One of the reasons I first started Lexapro was because it helped me modulate obsessive thought patterns which, more often than not, culminated in the unshakeable feeling that something, and sometimes, everything, was wrong. The challenge of coming off of the drug lies in determining whether that feeling is somehow intrinsic or resonates as a response to a particular experience. It would be disingenuous to say that there is a residue of violent nation-making within Outback Steakhouse. Neither the Kookaburra Wings nor the Chocolate Thunder from Down Under call specific attention to the ills of nationalism. Instead, it is perhaps truer, even if amorphously so, to say that the vibes, in all their staggering inauthenticity, were simply off.